A brief summary of Dr. Doug Sobey‘s (Research Associate of the Institute of Island Studies at UPEI) most recent work, the analysis of the fieldbooks of Alexander Anderson, the surveyor for Prince County from the 1830s to the 1870s.

Today it is difficult to envisage the appearance and composition of the old-growth forests that once covered the whole of Prince Edward Island before the arrival of European settlers in the eighteenth century. It is true that there are a few sites, such as the less disturbed and long protected Townshend Woodlot near Souris, that can give us some idea of the make-up and appearance of the pre-settlement forest, but elsewhere on the Island almost all of the remaining forests, dominated as they are by early successional red maple, trembling aspen, white birch and white spruce, bear no comparison with the pre-settlement forests that once covered the same areas. And this is especially true for the area west of Summerside.

By 1935, when the first aerial photographic survey of the Island was carried out, only 29% of this area (which I have called the Island’s ‘Western region’) was still under forest – meaning that over two-thirds of the pre-settlement forests had been cleared to create farmland. And, of the area’s ‘upland’ forests – i.e. those occurring on well-drained soils – more than 90% had been destroyed. The forest that remains, very heavily disturbed and much altered in its tree make-up, is mostly on the wetter poorly-drained soils that are unsuitable for farming.

It is thus fortunate that for that very part of the Island there happens to survive in the PEI Public Archives a unique and valuable source of information on its pre-settlement forests. This is in the form of the 55 fieldbooks of the land surveyor Alexander Anderson of Sea Cow Head who from the 1830s to the 1870s was the government surveyor responsible for most of the surveys in the Western region.

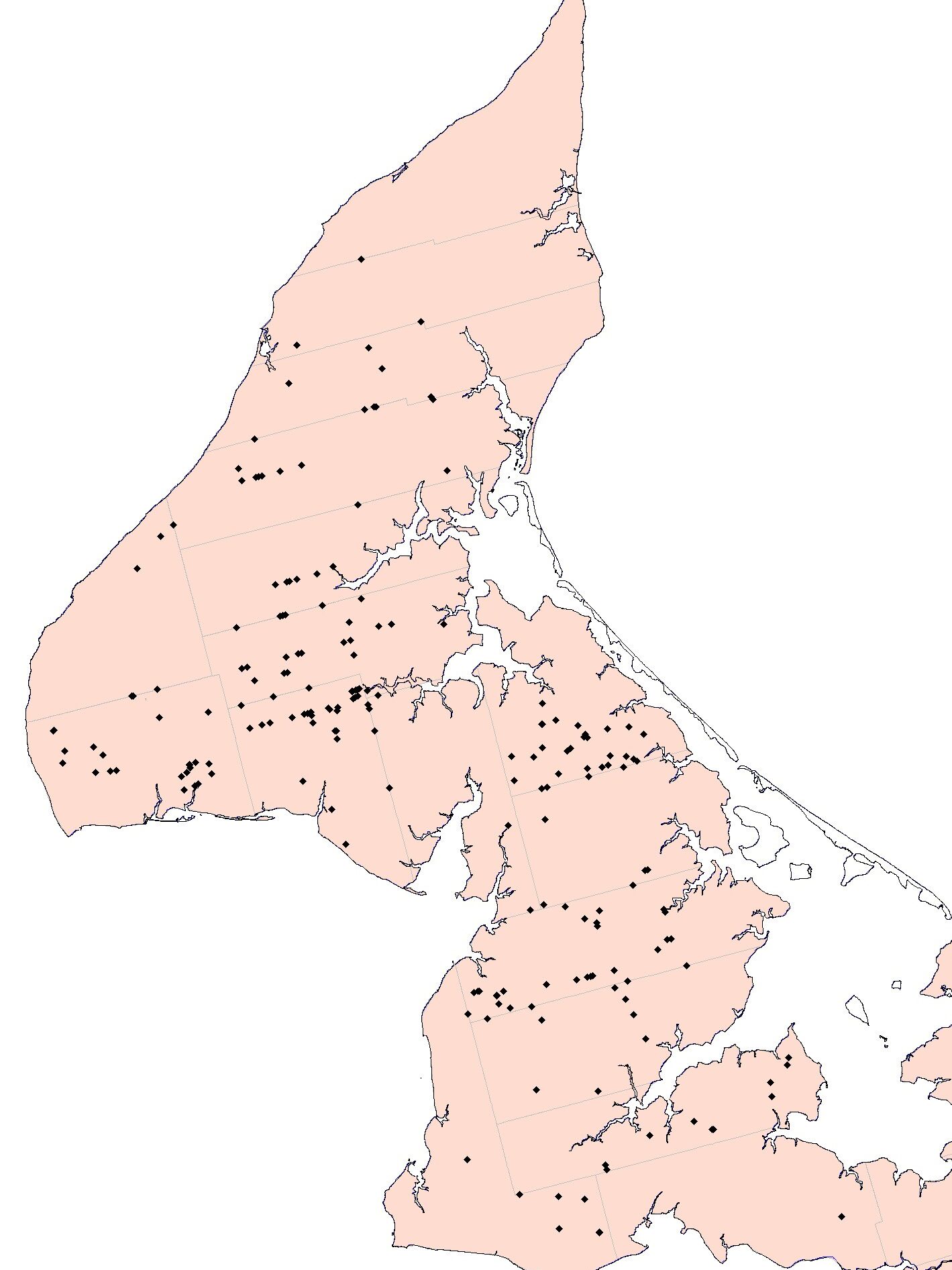

Analysis of the 2,375 forest stand descriptions that Anderson recorded in his survey books, including their plotting on a modern GIS map of the Island, has expanded our knowledge of the region’s pre-settlement forests well beyond what I had already been able to glean from analysis of other historical data for the region, such as the few contemporary descriptions of the forest (dating from the 1750s to the late nineteenth century) and the forest descriptions recorded on 30 nineteenth-century surveyors’ maps.

A satellite view of the Western region of Prince Edward Island (taken from the GeoReach PEI website). Forest now covers more than 55% of the region’s land area; much of this is secondary forest that has developed on abandoned farmland.

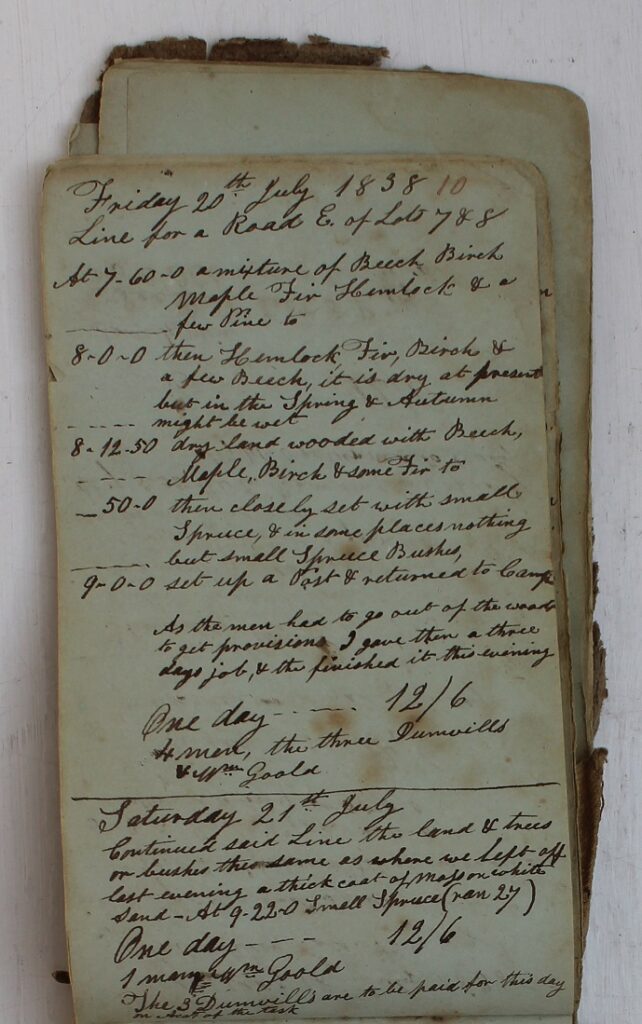

A page from one of Alexander Anderson’s fieldbooks showing his records of the forests along part of a line that would later become the O’Leary Road, as recorded on 20 July 1838.

The analysis of Anderson’s records has resulted in the identification of 18 distinct pre-settlement forest-types, most of which no longer occur in the region: nine are in ‘upland’ habitats and nine in ‘lowland’, upland referring to the region’s dryer well-drained soils, and lowland to its imperfectly-drained, and especially its poorly-drained soils. On the dryer soils upland hardwood forest, upland mixed forest, and various types of upland conifer forest were present; on the wetter, the boreal element of the Island’s tree flora was predominant, comprising species such as black spruce, white-cedar, and tamarack, as well as alder woods, barrens, and a lowland mixed woods in which ash (presumably black) was a major contributor.

Analysis of their soil drainage indicates that these forest-types make ecological sense, and they correspond to forest-types recognized in modern forest classifications elsewhere. A special analysis carried out to determine the relative contribution of the three shade-tolerant hardwood trees to the region’s upland hardwood forests indicates that American beech was the leading hardwood tree and it often occurred in the form of pure beech woods.

Comparison with the present-day forests reveals a great decline in – or even the complete loss of – several trees characteristic of old-growth upland forest, notably of American beech, eastern hemlock and eastern white pine, all common and widespread in Anderson’s records. Natural stands of white pine and hemlock are now virtually absent from the Western region, while beech, although still present in scattered stands, has been decimated, above all by forest clearance for agriculture (beech was a sign of good farming land) but also by forest fire (because of its thin bark it was especially sensitive to fire) and selective harvesting for firewood (beech made the best firewood). The final blow, and it was a major one, came in the form of beech bark disease which arrived in the 1920s and killed off most of the adult trees, leaving only ‘cankered’ stems sprouting as root suckers.

The white pine had been selectively harvested even before Anderson’s day for local use but especially for export to Britain, though Anderson was careful to record its past presence in the form of cut stumps. Hemlock, although not often exported, was harvested for local use, while some trees and stands must have been destroyed simply for its bark, to be used in tanning.

The other principal trees of the old-growth upland forest (sugar maple, yellow birch and red spruce) are still present in the small remnants of upland forest that remain today but nowhere are the trees of the size or age which Anderson would have come across. And, the maple and birch are nowadays rarely dominant in the region’s surviving hardwood stands, having been pushed into third or even fourth place by the ubiquitous red maple and other early successional trees such as white birch, trembling aspen, white spruce, and balsam fir.

The trees of the lowland forests, especially those on poorly-drained soils which have been largely spared from clearance for farmland, have fared better than those of the upland forest, though black ash is now a rare tree compared with its status in Anderson’s day, and white-cedar and black spruce, on account of being harvested for fencing, construction wood, and – especially the spruce (both black and red) – for shipbuilding, now generally occur as small trees, while the same early successional species that occur in the upland forests are now also very prominent in the lowland forests. The black spruce on very poor barren land (whether very wet or very dry) has been the least affected and likely still appears very much as Anderson would have seen it, apart from the effects of fire.

Thank you to Dr. Doug Sobey for sharing this insightful article about PEI’s pre-settlement forests with us to share.